With House of Fraser entering administration, Debenhams announcing the closure of up to 50 stores and accessories chain Claire’s thought to be following suit, the UK’s high streets are under unprecedented pressure.

This year has seen the greatest number of store closures since Woolworths collapsed a decade ago, with 1,500 retail units left empty.

As people increasingly shop online, traditional “bricks and mortar” stores are struggling to compete with the likes of Amazon and ASOS, while some commercial property investors opt to steer clear of retail. Some retailers have suffered from poor management or being saddled with debt having been bought by private equity firms, leading to closures.

Chancellor Philip Hammond attempted to address some of these issues in his recent Budget by announcing the formation of a dedicated high street task force to develop “innovative strategies to help high streets evolve.”

Meanwhile, the Treasury has announced £900 million in business rates relief for small retailers, as well as £675 million to pay for local projects, such as improving high street transport links.

But two recent reports indicate that fears about the demise of the UK high street may be premature – and that its future is safe in the hands of the “dialled in”, tech-savvy millennial generation.

A survey of 2,000 people aged 18 to 35 carried out by I-AM, highlighted by Ashby Capital CEO Peter Ferrari in his recent Property Week column, revealed that 74 per cent of millennials preferred visiting physical stores to online shopping. The report also found that 80 per cent of millennials had been shopping as a day trip within the past month.

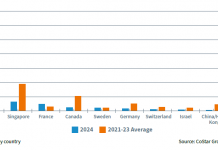

Meanwhile the findings of this year’s Midsummer Retail Report, from global real estate consultants Colliers International, also confounded many of the traditional assumptions about young shoppers.

Colliers commissioned YouGov to canvass the views of 3,000 shoppers aged between 18 and 80 and found that 78 per cent of 18-to-24-year-olds named the town centre as being their favourite shopping environment – compared to the 55 per cent of over-45s who said likewise.

“The current retail environment is not all about mass closures – it is actually about rapid evolution,” says Nick Turk, retail director for the South West and Wales at Colliers International.

“Barely a day goes by without another warning that retail is dying and that millennials only want to shop online, but we have now seen two major pieces of research which disprove that theory. Clearly millennials, along with other generations, do enjoy visiting their local high street and spending money.

“Although buying online is convenient and low cost, it can’t offer consumers the same experience as a physical store. While many transactions may be shifting from physical stores to online, there is very much still a place for shopping as an activity.

“We are social animals and consumers want – and need – engaging social experiences that can’t be bought online or found at home. Food and drink outlets, hair and beauty salons, cinemas, gyms, temporary events, seating and pop-ups can all help to transform retail areas into dynamic destinations.”

Nonetheless Nick Turk says the fortunes of the West’s town and city centres will inevitably vary when it comes to retail.

“There is a polarisation between ‘the best and the rest’ retail space which is becoming increasingly apparent. The dominant centres in the region, such as Bristol, Bath, Cheltenham, Exeter and Plymouth, continue to benefit from good levels of demand and a relatively low level of vacancy.

“Furthermore, there are major new developments coming on stream, such as the new 115,000 sq ft John Lewis department store in Cheltenham and the £40 million, 100,000 sq ft leisure extension to Drake Circus in Plymouth, which will be anchored by a 12-screen Cineworld IMAX cinema.”

Nick Turk says the key to the survival of our high streets is innovation and improvisation.

“These surveys highlight the fact that it’s imperative that high streets re-position themselves to become places that people will want to go back to, with the right mix of leisure, food and retail.

“This is what is being discussed in regard to the transformation of Oxford Street in London, the UK’s premier high street. This envisages prime retail units being retained at street level, on the ground floor, whereas the upper floors of many buildings can be used for a variety of other purposes.

“Another option is co-working, which is becoming increasingly popular but where outside London, supply does not meet demand. Providing modern working facilities with high-speed wi-fi in former retail premises is an ideal way of bringing people back into town centres.

“This is likely to be easier in a city like Bristol than in Bath or Cheltenham, which have many old buildings which would be difficult to convert.”

Nick Turk pinpoints the issue of ownership as being key to determining the long-term fate of many high streets.

“Where there is single ownership, with one landlord owning the majority of a high street or an entire shopping centre, then it is obviously far easier to bring about some kind of transformation.

“Where the ownership of shops is fractured with different landlords having different aims, which is the case in many towns in our region, then it will be much more difficult to create a co-ordinated transformation.”