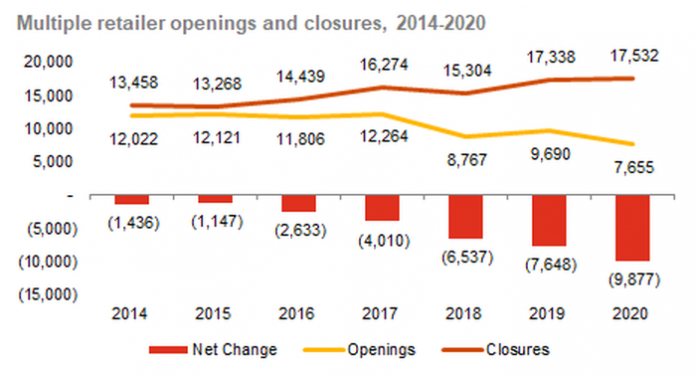

Almost 10,000 chain stores disappeared from Great Britain’s retail locations in 2020. In total, 7,655 shops opened, compared to 17,532 closures, a net decline of 9,877, according to PwC research compiled by the Local Data Company (LDC). Although a decline was to be expected in a pandemic this is the worst ever seen with an average of 48 chain stores closing every day, and only 21 opening.

The findings starkly compare to five years ago in 2015, which saw net decline of just over 1,000, 50% more openings and 25% fewer closures than 2020.

Worryingly the real impact of the pandemic is yet to be felt as some stores ‘temporarily closed’ during lockdowns, but considered as open in the research, are unlikely to return. But while we wait to see the full impact of COVID-19 on store closures, its effect on consumer behaviours are driving changes.

Retail parks have seen the smallest number of net closures of any location (453), compared to high streets (4,690) and shopping centres (1,791). Footfall was already holding up better in retail parks before the pandemic due to their investment in leisure and some retail parks have benefitted by being anchored by essential retailers that have remained open, even during the tightest restrictions. But it’s also because they’re considered safer in the current environment: free parking means it’s possible to drive to the location (and avoid public transport), outdoor areas mean reduced indoor mixing and larger units allow for better social distancing measures.

Shopping centres by contrast, are often poorly located for consumers who want to shop local and travel less to city centres, and are more likely to host fashion retailers and chain restaurants, which are the number one and thee most hard hit categories for net closure in 2020. Meanwhile, the drop off in high-street footfall has affected those multiple retailers located on high streets, particularly those in large city centres. However, this decline in multiples has been somewhat offset by growth in interest of local and independent operators.

Small towns, which have long been in decline at the expense of more populous areas and cities, are now also enjoying a mini-renaissance. Consumers now want to shop in these locations, and larger retailers want to be there.

There is greater regional disparity this year. Looking at absolute figures, London, South East and the North West have seen the most closures, unsurprising given those regions have more chain stores. However, London has undoubtedly been hit harder than other regions, with a record 5.8% increase in net closures this year. Conversely, Wales, Scotland, East of England and South West, where retail destinations are less highly concentrated, have been more protected from closures.

This is a reversal of fortune over the last few years when chain retailers focused on more populous and prosperous regions, such as London and the South East. However, 2020 has seen London and the South East accounting for a third of the decline of all shops, even despite the South East remaining partly protected by the displacement of London shoppers as commuters work from home.

City centres are now faring worse than suburbs and commuter towns, and shopping centre shops are twice as likely to close as retail parks. This shift in how retail locations have been affected is being driven by the number of people working from home.

With fewer people visiting, city centres, such as Birmingham, Bristol, Leeds and Newcastle, have seen an almost 8% decline in multiple stores. While London does fare slightly better (-7%), its performance is inflated because of the inclusion of its suburbs, as well as the City and West End, which have seen footfall decline faster in the past year.

Suburbs across the UK have done better, as have commuter towns in the South East and East of England, such as Slough, Orpington, Harlow and Welwyn Garden City. There have also been fewer closures in the smallest towns and seaside towns, such as Scarborough, Eastbourne, Great Yarmouth and Llandudno.

Lisa Hooker, consumer markets lead at PwC, said;

“For the first time, we’re seeing a widening gap between different types of locations: city centres and shopping centres are faltering, but certain retail parks with the right customer appeal are prospering.

“Location is more important than ever as we see a reversal of historical trends. For years, multiple operators have opened more sites in cities and closed units in smaller towns. As consumer behaviours and location preferences change, partly as a result of COVID-19, retailers are moving to be where they need to be. Small towns will remain important but we can expect recovery in cities as workers and tourists return, albeit in smaller numbers adopting more flexible working models.”

On a sector by sector basis, whilst net growth of the top 5 categories is between +21 and +88 units, no other categories showed net growth of more than +2 units. Only eight categories saw any growth, 11 were flat, and 80 declined.

Despite the uncertainty and volatility of the past year, some operators are still expanding and finding the right physical stores in the right sector and the right location. For retail, the best performing categories include convenience, discount or essential operators, general merchandise value retailers that don’t typically sell online, and local services that need to be located nearby, such as tradesmen or repair shops. For leisure, ‘convenient leisure’ categories have grown through takeaways, cake shops and even coffee shops. However, while coffee shops might traditionally be thought of as city centres units, any decline there has been offset by growth in drive-in coffee shops in retail parks and out of town locations.

Lisa Hooker, consumer markets lead at PwC, continued;

“The effect of COVID-19 is yet to be seen on most categories as much of the impact we’ve seen this year is a reflection of things that happened before the pandemic. This was not just the move online but areas such as legislative changes, e.g. for betting shops, consolidation due to previous overexpansion, or chainwide closures for restaurants and mobile phone stores that found themselves in trouble pre-COVID-19.

“The full extent will be revealed in the coming months as many of the CVAs and administrations in the early part of 2021 still haven’t been captured, including department stores, fashion retailers and hospitality operators that will leave big holes in city centre locations. Retail and leisure operators must take action to ensure they are in the right places, so they’re not left surrounded by empty units and shopfronts.

“However, there will be big opportunities for growth into the gaps that are emerging. After the global financial crisis we saw growth of discounters and foodservice chains that replaced exiting retailers. There is an opportunity for operators who can find the right location at the right time to thrive, even despite the current uncertainty.”

Lucy Stainton, Head of Retail and Strategic Partnerships at The Local Data Company said;

“2020 has been an undeniably challenging and transformative year for the physical retail and leisure landscape and the acceleration of chain store closures seen in our latest research is unlikely to surprise many.

“With the restrictions in place during each of the three national lockdowns, only c.17% of the market was classed as ‘essential’ and thereby permitted to trade. However, the damage to footfall in some city centre locations and particularly in London meant that a number of chains opted to temporarily shutter their stores irrespective of their ‘essential’ status. The question now becomes – have we seen the worst of the damage? These numbers only include store closures we know to be permanent and when government support schemes end, we expect a further increase in store closures before the picture starts to improve.

“Looking at where this opening and closure activity has predominated really tells the story of changing consumer preferences and shifting demand. On the whole, flagship city centre high streets and shopping centres saw a greater decline in chain stores versus more local markets and retail parks which proved to be more convenient and perceptibly safer. With this in mind we absolutely believe that after the short-term shake-out, there will be huge opportunity for acquisitive brands who are either looking to launch in different types of locations with new concepts or, take advantage of newly available space in their core markets.”

Zelf Hussain, retail restructuring partner at PwC, said:

“Government roadmaps across various parts of the UK are set to reactivate the high street. But it’s going to look very different post- Covid as businesses will have to weather the twin impacts of permanently changed shopping and working environments.

“Companies must also run the gauntlet of rent payments and the eventual return of landlord enforcement powers and creditor winding up orders – all whilst trying to bankroll the costs of reopening, general operations, dealing with different regional rules and maximising revenues in what is set to be a fiercely competitive market.

“So although we are upbeat about a bounce back for the high street we will also see restructurings on the rise as companies look for sustainable solutions; PwC tracked 29 major CVA launches in the retail consumer hospitality and leisure sectors in H2 2020 alone vs 4 in H2 2019. More will follow in 2021 – alongside new tools such as the Restructuring Plan- as U.K. businesses simply aim to survive before they can flourish.”